For Americans wanting to live or travel extensively in Europe, finding a way to stay beyond 90 days is the major sticking point. Lisa Crawford, an Air Force retiree, found a way. Two ways, actually. She obtained residence in Malta and, later, in Italy, all the while taking full advantage of the opportunity to travel throughout Europe.

Lisa quit her post-military job at age 50 and has been traveling full-time ever since. In Part 1 of this two-part interview, she told us the story of why she fully retired much earlier than planned, and she shared her adventures traveling the U.S. in her RV.

In Part 2 Lisa gives us the scoop on moving to Europe and continuing her dream of living as a nomad in retirement.

When we left off in Part 1, you had just decided to sell everything you owned to move overseas. How did you decide to take that big step?

I’m often asked why. Why quit your job? Why travel in the RV? Why move overseas?

My short answer is always:

“Why not?” or

“Because I can.”

The longer answer is this: I was a Hospice volunteer. I sat with people who were near the end of their life, and they knew it. The one regret almost every single person expressed to me was not for mistakes they made or things that didn’t go as planned. It was for the chances they didn’t take, or the things they wanted to do but didn’t.

I’d much rather look back on my life and wonder, “What the heck was I thinking?”

As far as getting rid of almost everything I owned, I realized possessions were just stuff. I can’t express how liberating it was to get rid of almost everything.

Of course, I kept a few irreplaceable items, like family heirloom furniture, photo albums, and some large framed photographs, but the rest . . . donated!

Was packing up your life to move overseas easier or harder than transitioning from your apartment to the RV?

Easier for sure, because I had already done it once.

After the flood, I became a bit of a minimalist, in part, because I had very little space. I rarely bought anything that I didn’t have a practical need for. As a Habitat for Humanity volunteer, most of my storage space was used for tools.

Your first destination was Malta. You were able to rent an apartment and get settled almost immediately. At that point, did you still have only a 90-day tourist stamp?

I tend to do things on a whim. I did virtually no research on what it took to live in Malta, in part because I didn’t intend to stay.

I went to the agency looking for a 3-month lease. It wasn’t until I said I wanted the apartment she had shown me that the agent told me it was only a 6-month lease. Honestly, I figured I’d stay 3 months and worry about it later. Worst case scenario, I break the lease and she keeps my deposit.

It literally took one day to get set up. I went to a rental agency in the morning, saw this apartment, got the key, stopped by the shop to set up cable and WiFi, and moved in that night. No one ever asked for anything other than my passport.

How did you obtain residency in Malta? What was involved in the application process, and how long did it take?

There is a joke among most expats, no matter where they live, about the wide-eyed tourist who sees a place on vacation or in a movie and thinks, “Yeah, I’m moving there.” I admit, that idiot was me!

Schengen zone, tourist visas, residency, hmmm, what’s that about?

Well, Google was my friend. Plan A had always been to stay 3 months, and then go to another country for 3 months, and so on. I realized that plan wasn’t going to work because of Schengen.

| Related Reading: Obtaining a Spain Retiree Visa

Schengen is a travel zone, comprised of 26 European countries. There is no passport required to pass between these countries but strict border control to get into and out of Schengen. The critical rule for American tourists is that you can only stay inside the zone for 90 days in any 6-month period of time.

All of the countries I wanted to visit were inside Schengen. Overstaying the 90 days can get you banned from all 26 countries for 7 years.

There is a long and aggravating story, but the short version is this:

I talked to the folks at Identity Malta (the immigration office), who said I should apply for economic self-sufficiency residency. I filled out a form, gave them the requested documents proving I had enough income to support myself, proof of medical insurance, a copy of my lease, and a copy of my passport. I could stay in Malta past the 90-day limit as long as my application was pending.

Several months later it was approved, and I was officially a resident for the next 2 years. One key requirement of this type of residency is you can’t work. That’s why you have to prove you are self-sufficient.

How did you become part of the community in Malta? Did you have many local friends, or were your friends primarily expats?

Malta is a fantastic place for expats; you make friends from all over the world.

I made my first friend when we joined a hiking group. We bonded when the much faster hikers left us behind within the first 15 minutes. She invited me to a dinner with other expats, and they, in turn, invited me to more events. A few months after I arrived, I started dating a Danish guy I met at one of the expat events.

The rest is history. It’s a small island, and most of the groups overlapped, so everyone knows everyone.

I did have a few Maltese friends, but most of the people I knew were expats. I had a fantastic Maltese neighbor whom I enjoyed long hallway conversations with.

Tell us about life in Malta. How did you spend your time?

By the time my residency was approved, I had been dating my boyfriend for several months. One reason we got along so well was that he also loved to travel.

The day I got my residence card, we booked a trip to Barcelona. From then on, we traveled about once a month to places all over Europe. Since he still worked, (he owned his own business), we could only stay 3 or 4 days at a time, but we packed in as much as possible.

When not traveling, I was very active with friends: boat trips in the summer; BBQs by the sea; random meetups for lunch or dinner; or just seeing the sights on Malta.

Our apartment was one of the largest among our friends, so it was the natural place to host parties, dinners, and weekly game night.

I also hosted three Thanksgiving dinners with all the traditional fixins for about 30 non-American friends. (They all turned up their noses at the thought of sweet potato casserole with marshmallows. But the next year, they staged a very vocal revolt when said marshmallows were omitted by a fellow American).

There were regular Friday night drinks with one group and hiking and book club with another. One friend hosted weekly bowling night, movie night, and coffee mornings.

I did assorted volunteer projects: giving talks to elementary school kids as part of an outreach program for the U.S. Embassy; beach cleanups; a bit of work with a local shark education group; some work at a horse rescue; and I was set up to become a trainer and work with refugees for the Red Cross.

How did expat living in Malta compare to what you envisioned when you decided to move to Europe? Any moments of regret after you moved there?

I never imagined the amazing friends I would make. It was really easy to meet people. There were a lot of Meetup and Internations groups. Everyone was very friendly and welcoming, probably because we all had the same experience of leaving family and friends and coming to a new place. It reminded me a lot of the military, no doubt for the same reason.

I never regretted moving to Malta from the U.S, but I did get tired of living on an Island. Although I traveled quite a bit, it was always a bit of a process, having to fly everywhere. I’d much rather be in a more central location, where I can hop a train for a day trip.

One nice thing: English was an official language, so everyone was bilingual. Maltese is very difficult to speak. Even if you try to learn, often they will say “please stop, you’re hurting my ears.”

My neighbor was pretty patient and taught me a few phrases.

Your original plan when moving overseas was to earn money by teaching English. But your Malta self-sufficiency residence didn’t allow you to work. Did that concern you?

It didn’t concern me that I couldn’t work. The cost of living in Malta was so cheap, especially once my boyfriend and I moved in together.

Like most of my plans, teaching English was quickly replaced with something else.

You applied to renew your Malta residency after 2 years, and it didn’t go as smoothly as the first time. What happened?

Like most countries, even the U.S., navigating government bureaucracy can be a challenge.

There is a word in Maltese, mela. It has about a million different meanings, but one is “yeah, so?”

My residency was set to expire in late January, so in early December I went back to Identity Malta with the forms and documentation I had been told I needed. The website had clear instructions for renewing under the economic self-sufficiency program. I immediately got the runaround.

First, I was given a different form, asking for different documentation.

“But this is not what the website says and not what you specifically told me 2 weeks ago.”

“Mela.”

As I was gathering the new information, I noticed the form was for Global Residency. Under this program, I would have to pay a €6,000 fee and at least €15,000 in taxes.

Another visit to Identity Malta, and I was told the self sufficiency program no longer existed.

“That’s not what your website says and not what you told me 2 days or 2 weeks ago.”

Same person, same answer: “Mela.”

I asked for a supervisor, who said self-sufficiently no longer existed. I could do Global Residency or Malta Residency and Visa Program (MRVP).

Under MRVP I would have to buy property worth €320,000, pay a €5,500 non-refundable application fee, invest €30,000 for at least 5 years, and have an annual income of €100,000. Of course, the details of both programs differ, depending on which government website you look at or which government agency you ask. To be fair I think the MRVP was a new program.

The local newspaper, Times of Malta, got involved and was told the self-sufficiency program was valid and could be renewed.

At the end of the day, I was a visitor to their country, and it was pretty clear they didn’t want to renew my residency unless I was willing to pay large sums of money.

I just checked their website, and they still have the economic self sufficiency program. A new requirement: if you are not applying for the two above-mentioned programs, you must prove significant social or economic ties to Malta.

How did you decide to move to Italy, and what type of residence did you get?

I honestly picked Italy, in part, because it was the next country up. Remember the original plan to live in many different countries? May as well be somewhat methodical about it.

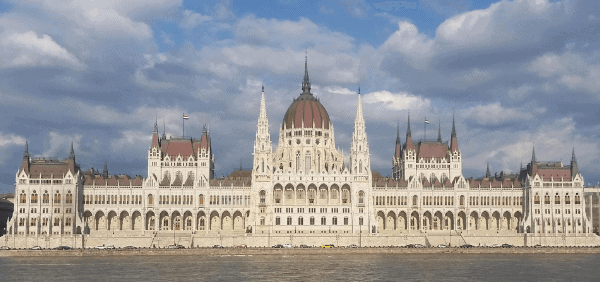

Plus, Rome was a major hub, and they had frequent and cheap flights to Malta. And of course, who wouldn’t want to live in Rome?

Much like my initial request for residency in Malta, I filled out a form, sent it in, and eventually it was approved.

I received a permesso di soggiorno, or permit to stay, which is a 1-year residency. Basically, it had the same requirement and terms as in Malta; I had to prove I could support myself, prove I had medical insurance, and provide a lease. I was not allowed to work.

One big difference to Malta, and the difficulty for most Americans: you have to have a long stay visa before you apply for the permesso di soggiorno.

The visa is only required if you plan on staying more than 90 days, and the kicker is, you have to have it before you move to Italy. It can only be issued by your country of residence.

Before I flew to Rome, I visited the Italian Embassy in Malta. No mention at all of this requirement. I got to Rome, found this out, and flew right back to Malta. The thing that saved me was I was still a resident of Malta, so I got the visa in one day, after talking to the right person.

If you go through the Italian embassy in the U.S., it can be a 6 -12 month wait. And a lease is one of the requirements, so you can end up paying for an apartment that you can only visit for 3 months.

How did expat life in Rome compare to Malta?

The expat life in Rome was different for several reasons.

First, Malta was so small, everyone knew everyone. That was hardly the case in Rome.

Second, there was a language barrier. In Malta, although there were people from many different countries and many different languages, people unofficially agreed to all speak English.

In Rome, I joined several groups but found mostly Italians and mostly men. Which would have been great, I would love to have had Italian friends and help learning the language. What I noticed was they were more than willing to speak to the more attractive women, but mostly ignored me. What I heard a lot of women complain about was that the Italian men used the groups as a hunting ground to pick up foreign women.

I was finally able to find a great hiking group with a much better mix of nationalities and much friendlier. I also volunteered at a soup kitchen and finally made a wonderful Italian friend.

I took an intensive Italian course, studied on my own, and took private lessons.

I was a complete failure! I simply couldn’t learn it. I know part of my isolation was my own fault, because of my lack of ability to speak to people.

So, Italy was much worse in terms of the social aspect.

Tell us about the dog-sitting business you started. How did you get it going?

Well, one rule of my permesso di soggiorno was that I not work, so shhhhh.

That being said, living in Rome was significantly more expensive then Malta, especially if you consider that I was sharing rent there, and now I was on my own. Plus, my boyfriend and I were still traveling together at least once a month, and I took full advantage of the opportunity to explore Italy.

| Related Reading: How to Become a Pet Sitter

I had been dog sitting for friends in Germany and in Malta for free. I saw a post on one of the expat Facebook pages looking for a dog sitter, and that’s all it took.

I originally was only going to charge a nominal fee because honestly, I just loved dogs and it was fun. But the going rate was €30 a day, and the first few people insisted on it.

Hey, who am I to argue?

Apparently, there was a huge need, and my name just got passed around. Before I knew it, I was at a different house every week and even had bookings into the next year.

You only stayed in Italy for 8 months before trying to move back to Malta. Why?

Mostly because I missed my boyfriend.

Also, because I just couldn’t learn Italian. I didn’t want to live in a country where I was never going to learn the language. It seemed really arrogant to expect everyone else to speak English.

If you are a resident of one Schengen country, you can be in another one past the 90 days. Technically I would still be an Italian resident, but I’d be living in Malta.

Once I moved back, I visited Identity Malta again. I found out that since my boyfriend was an EU citizen, and we had been together for more than 2.5 years, I could be granted residency as an EU partner.

I had to submit proof of our romantic relationship: things like pictures of us together, a joint lease, letters from friends, and hotel and airline receipts. I handed in a notebook with about 100 pages and asked what my chances were. The guy laughed and said he’d never seen this much documentation. He said they were really backed up, it could take up to 6 months.

This time I was dealing with a different office, EU vs Non-EU and they certainly seemed to be more knowledgeable and helpful.

How did you feel about living in Malta the second time around? Did you like it as much?

It was really nice to be home with my boyfriend and my friends. It did feel like coming home, but it also felt like coming back to an island. I missed the freedom that I had in Italy to just hop on a train and go on a day trip. If I didn’t get residency in Malta the second time, my plan was to move to Germany.

After about 6 months back in Malta, you went on an extended tour of SE Asia. How did that come about?

When I lived in Rome, one of my friends, Caron, was a tour operator for one company and had her own business where she designed individual boutique tours. She mentioned that she was going to SE Asia for 3 months in her off season and invited me along.

Or maybe I invited myself.

It was the trip of a life time for sure. It was my first time traveling for an extended period of time with anyone and, although it had its ups and downs, it was the most fun trip I’ve ever been on.

Having a person who designs travel for a living was the icing on the cake. It was so nice to just sit back and go where she told me. We went to Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and Kuala Lumpur together. We split up because she had to get home, and I went to Singapore, Hong Kong, and Borneo.

What was it like being on the move constantly vs. having your own apartment to come back to? Did you enjoy being on the road?

It was exhausting, but I absolutely love it, like it was what I was born to do!

One really smart thing Caron did was schedule a month in Chiang Mai, Thailand around the mid-point in the trip.

We had been on the move constantly, usually 3 or 4 days in each place, then on to the next adventure. Mind you, I’m not complaining at all. You develop a bit of a routine no matter where you are. We were usually in one place long enough that we didn’t have to rush to see everything in 1 or 2 days.

The month-long break gave us time to really get to know the city and make some friends; not just move from one place to another. It was also really nice to unpack completely and do laundry in an actual washing machine. We had been washing out our underwear and any really, really dirty clothes in the sink. Except that time in Cambodia where I had bedbugs and found an actual dryer . . .

One benefit of not living in an apartment is that you don’t have the day-to-day chores you do at home. No cooking, cleaning, laundry, shopping, etc. — that pressure you feel to be productive.

Picking out what clothes you want that day is easy too: which is the least dirty of the five choices I have?

After you returned from Asia, how much longer did you live in Malta?

While I was in Asia, my boyfriend and I decided to go our separate ways, but we parted as friends.

I went back to Malta for a week and gave him everything in exchange for half the cost of shipping four boxes back to the U.S.

Meanwhile, my latest residency request had been denied.

Why didn’t you move to Germany, as planned?

While in Chiang Mai, Thailand, I met many people who were full-time travelers.

Remember, that had always been my original plan. I had always envisioned I would have a base in each country and travel a bit from there. After meeting so many people that were just traveling full-time, living out of a suitcase, I realized that was a better option for me. It’s expensive to maintain a home while traveling as extensively as I wanted.

Without my boyfriend to tie me down, I was now free to do whatever I wanted.

I have a friend who lives in Scotland. I stayed with her for 6 weeks, and we had the most amazing time. I realized that I could have the best of both worlds. I could crash with her when I felt the need to have a home, but I’m also free to be gone for months at a time without checking in.

It’s also quite handy that the UK allows me to stay for 6 months at a time, versus the 3 months in the Schengen Zone. I can stay in Scotland, recharge my batteries, and enjoy the comforts of home, not to mention my amazing friend and the adventures that we have doing short trips around Scotland.

What are your current thoughts about full-time travel? Are you still enjoying it? Do you foresee settling down in the near future?

I am now a solo homeless nomad. I have no home, no country of residence, and no ties to anywhere.

I’m so excited to be a full-time traveler, going wherever the mood strikes me!

I decided to travel much slower since I’m now doing it full time. I’ll spend much longer in one location, so I can soak in the culture and vibe of a city and not just pop in and out. Staying longer is also more economical.

I’ll also be looking at more pet sitting, which is where I am right now, cat sitting in Omaha. Doing a long-term sit doesn’t make me any money but does offer me rent-free living and a chance at a home with all the benefits and none of the obligation.

I’m very excited about all the places I’m planning on going next: China, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and the islands of the south Pacific.

I’m on the lookout for compatible travel buddies to see if that works for me. I’m planning on Japan and Australia with a fellow retiree, just to give it a try.

Although I certainly like the freedom of being on my own, I realize just how much more fun having someone to share the experiences with made the last trip. There must be a happy balance of the two.

I see no reason to settle down in the foreseeable future. One big problem is: where would I even want to live?

If, in my travels, I meet another man, I’d no doubt stay a while, but this time he better be willing to go with me, otherwise it will be a short visit!

Do you have any advice for retirees considering a nomadic lifestyle? What can they do to make it more sustainable, not only financially, but in terms of quality of life?

I think the biggest hindrance is your mindset. Ask questions of fellow travelers, and do your research, but ultimately, you have to take the plunge and just go.

I meet so many people who say, “I would love to do what you do, but I can’t because . . . .”

If you wait for all the stars to align, you’ll likely find yourself dead or physically unable to travel.

Rent your house out, put your stuff in storage, quit that job you took after retirement because you didn’t know what else to do.

Kiss those grandbabies goodbye for a bit. Chances are pretty good they’ll be there when you come back.

Worst case scenario, you don’t like it and you go home.

As with RVing, use a mail forwarding service and change everything you can to paperless so you can access everything online.

Make sure your cell phone is unlocked so you can use SIM cards in each new country.

Get rid of the notion that you need to pack everything you own in the biggest suitcase you have. You would be surprised at how far you can go with just a few outfits. Mix and match, and realize that even if you wear the same thing every day, no one will know!

Get a blanket travel and car rental insurance policy for a year.

Don’t worry about being lonely. There are so many people to meet if you’re open. Be on the lookout for other travelers, and not just Americans. Anyone on holiday seems friendlier, for some reason.

Do day trips and be open to joining an existing group of friends. I met some wonderful ladies on a day trip out of Dubrovnik and visited them when I was in the UK.

Post on any of the numerous travel groups, asking if anyone is in whatever city you’re in. I met two people in Split, Croatia from such groups. Of course, the obvious care must be taken for making sure you stay safe.

Start a blog or online diary. You can keep your friends and family updated on what you’re doing without telling the same story to each and every person. It will also help you remember what you did and where. Believe me, you see enough places, and they blend.

Find good travel blogs and Facebook pages; they offer a wealth of knowledge, from travel tips and hacks, to advice on where to go and what to do. Don’t be stuck in the mindset that you can only follow military pages (of course they are the best!).

Bottom line and my motto: Life is short, you have to get the most out of it while you can. Don’t be afraid to just do it! The absolute worse case scenario is that you find it’s not for you, and you come home.

You can follow Lisa’s travels on her blog, Lisa’s Living Her Dream.

Related Reading

How to Become a House and Pet Sitter

Loved this two-part series. I didn’t realize we could become residents of other countries while drawing our military pension. I thought we had to be short-term visitors or in a government (or contract) position.

Thanks Julie! Yep, you can become a resident if you can cut through the red tape. You just have to be sure that the type of residence you obtain doesn’t make your military pension subject to taxation in your country of residence! Each EU country has their own laws and different types of visas.